Pride Month: A Sexual Health Guide for Gay, Bisexual and MSM

Every June, we celebrate Pride Month to remember the 1969 Stonewall Uprising in Manhattan. It’s more than just a celebration of LGBTQ+ identity, it’s also a time to talk about important issues affecting the LGBTQ+ community. Recent data from Public Health shows that sexually transmitted infections are increasing amongst gay, bisexual and men who have sex with men (MSM). Gonorrhoea cases have gone up by 9.4%, chlamydia by 8.2%, infectious syphilis by 7.3% and genital warts by 5.3%.

Therefore, to support sexual health in Pride Month, lets explore men’s sexual health, including sexually transmitted infections (STIs), HIV, window period, testing, treatment, prevention and more.

Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) in gay, bisexual and men who have sex with men (MSM)

Pride Month is an important time to talk about overall sexual health. Whilst many common sexually transmitted infections have increased in gay, bisexual and MSM, such as gonorrhoea, chlamydia and infectious syphilis, there have also been increases in less common sexually transmitted infections, such as lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) with an 15.9% increase as well as a staggering 48.5% increase of shigellosis - with some cases showing extensive drug resistance - demonstrating concerns for limited effective treatment options.

In May 2020, an outbreak of monkeypox was reported worldwide, with gay, bisexual and MSM being the most affected. Symptoms of monkeypox take hold within 5-21 days of being infected and include symptoms such as; fever or chill, temperature, headache and a rash that looks like pimples or blisters. While 2,500 cases were reported between 2021 to 2022 within England, there were only 137 cases reported in 2023.

HIV

HIV, or Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) is a virus that attacks the body’s immune system and makes it weaker. Public health data showed a 22% increase in new HIV diagnoses in England between 2021 and 2022, with the majority of cases linked to diagnoses made abroad but later confirmed in England. Despite a decrease in first diagnoses among gay, bisexual and MSM in England, there is still work to achieve a target of zero new HIV cases by 2030.

That’s why raising awareness about HIV and sexual health this Pride month is crucial. If left untreated, HIV can progress through a series of stages, from primary stage to late-stage HIV or AIDS. Whilst HIV doesn’t discriminate based on sexual orientation, gay, bisexual and MSM are mostly affected by the virus.

HIV can be transmitted through blood, vaginal fluid, semen and breast milk if someone has a detectable viral load. However, the virus doesn’t survive for very long outside of the body and it can’t be transmitted through spitting, kissing, coughing or sneezing.

What is the window period for HIV testing?

The window period is the time between when someone gets infected with HIV and when the virus can be detected by tests. During this time, the infection markers (like p24 antigen or HIV-1 and HIV-2 antibodies) might not show up on tests as the levels are too low. Different tests have different window periods, for instance blood tests taken in sexual health clinics often have a testing window of 45 days, whereas a self-taken finger prick test can have a window period of 90 days - which means different blood tests can tell you what your HIV status was either 45 days or 90 days ago.

Can I test for HIV earlier?

Yes, you can test earlier for HIV, but the result might not be entirely accurate. For instance, our INSTI HIV Self Test kit can be taken from 21-22 days of exposure to the virus, but it can take up to three months to produce a positive result - it all depends on how strong the antibodies are in your bloodstream. Testing for HIV is vital as if left untreated can continue to weaken the immune system, so it’s a good idea to get tested or speak to a professional as soon as possible if you think you are at risk.

To celebrate Pride Month, take charge of your own sexual health and find out your HIV status with our INSTI HIV Self Test … you can order it straight to your home here.

What is post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP)

PEP is a medication that is taken after potential exposure to HIV to prevent the virus from establishing itself in the body. PEP should be taken within 72 hours after exposure, but ideally as soon as possible - although it has a good chance of working, it’s not always guaranteed to work. PEP can be prescribed on the NHS for free, either through your local sexual health clinic, HIV clinic or if these clinics are closed (for instance a bank holiday or weekend) then you can pick it up through A&E.

Treatment for HIV

Whether you’ve been diagnosed with HIV this Pride Month or at any time, HIV treatment aims to lower the virus level until it becomes undetectable - as once HIV levels are undetectable, the virus can’t be transmitted to others. If the virus is detectable in your bloodstream, it indicates high levels of HIV and can be passed on from person-to-person.

HIV treatment usually involves taking antiretroviral medicine, which stops the virus from replicating in the body - allowing the immune system to repair itself and prevent further damage. Different combinations of HIV medicine work for different people, so some people only take a single pill of combined antiretrovirals, whereas others may take up to 4 tablets a day.

Regular blood tests are done to check your viral load, which tells us how well the treatment is working. Lower levels of the virus in your blood indicate that the treatment is effective for you, with the goal of making the levels undetectable. This means the treatment is doing its job in controlling the virus and reducing the risk of transmission to others. Although gay, bisexual and MSM are at higher risk of contracting the virus, anyone can be at risk of acquiring HIV.

How to prevent acquiring HIV?

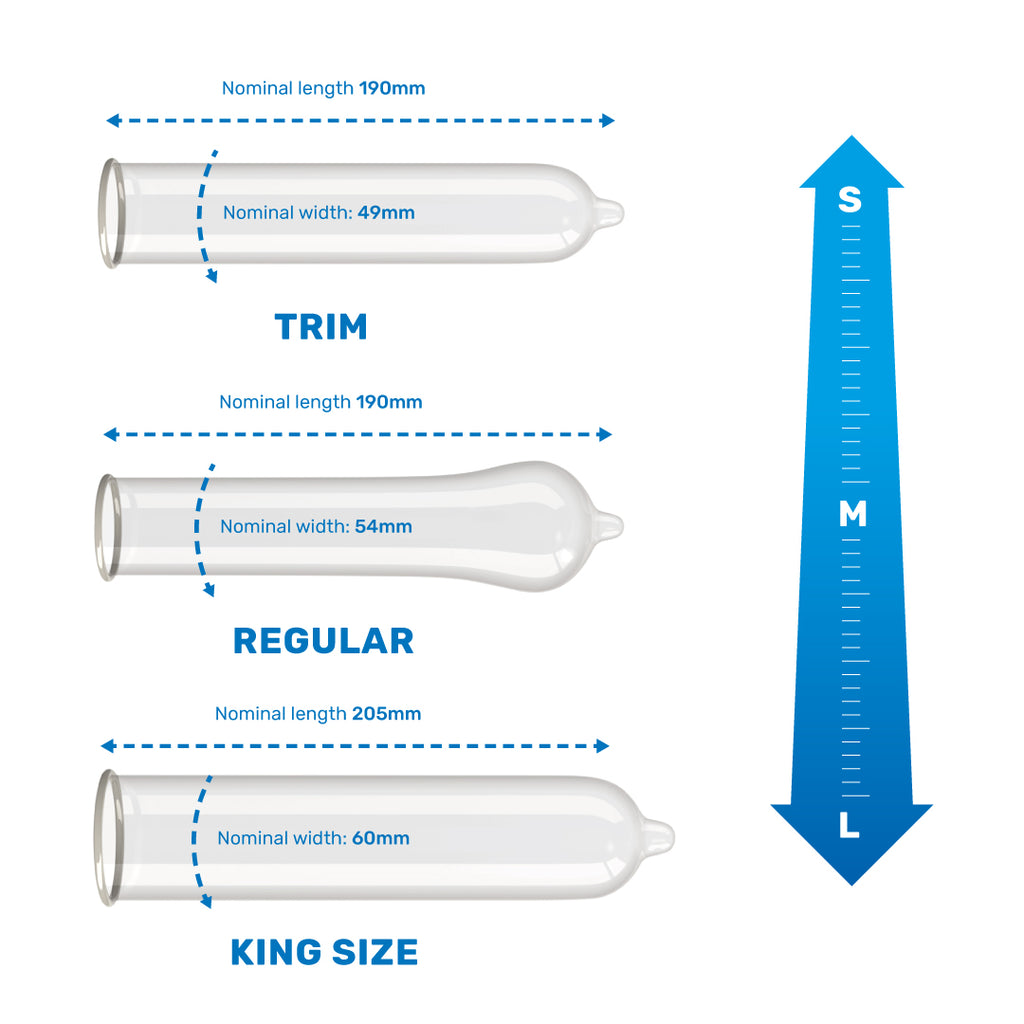

To protect your sexual health and risk of contracting HIV, always use a condom during any sexual activity. Condoms help prevent the transmission of HIV as they act as a barrier, preventing direct contact between bodily fluids such as semen and vaginal fluid, which could contain HIV. By stopping the virus from entering the body, condoms protect against HIV transmission, sexually transmitted infections and unintended pregnancy.